Martin Luther King Sunday (The Healing of Namaan)

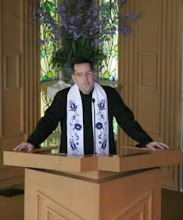

Rev. Roger Butts

January 19, 2003, Unitarian Church, Davenport

________________________________________

Reading

2 Kings 5:1-14

5:1 Naaman, commander of the army of the king of Aram, was a great man and in high favor with his master, because by him the LORD had given victory to Aram. The man, though a mighty warrior, suffered from leprosy.

5:2 Now the Arameans on one of their raids had taken a young girl captive from the land of Israel, and she served Naaman's wife.

5:3 She said to her mistress, "If only my lord were with the prophet who is in Samaria! He would cure him of his leprosy."

5:4 So Naaman went in and told his lord just what the girl from the land of Israel had said.

5:5 And the king of Aram said, "Go then, and I will send along a letter to the king of Israel." He went, taking with him ten talents of silver, six thousand shekels of gold, and ten sets of garments.

5:6 He brought the letter to the king of Israel, which read, "When this letter reaches you, know that I have sent to you my servant Naaman, that you may cure him of his leprosy."

5:7 When the king of Israel read the letter, he tore his clothes and said, "Am I God, to give death or life, that this man sends word to me to cure a man of his leprosy? Just look and see how he is trying to pick a quarrel with me."

5:8 But when Elisha the man of God heard that the king of Israel had torn his clothes, he sent a message to the king, "Why have you torn your clothes? Let him come to me, that he may learn that there is a prophet in Israel."

5:9 So Naaman came with his horses and chariots, and halted at the entrance of Elisha's house.

5:10 Elisha sent a messenger to him, saying, "Go, wash in the Jordan seven times, and your flesh shall be restored and you shall be clean."

5:11 But Naaman became angry and went away, saying, "I thought that for me he would surely come out, and stand and call on the name of the LORD his God, and would wave his hand over the spot, and cure the leprosy!

5:12 Are not Abana and Pharpar, the rivers of Damascus, better than all the waters of Israel? Could I not wash in them, and be clean?" He turned and went away in a rage.

5:13 But his servants approached and said to him, "Father, if the prophet had commanded you to do something difficult, would you not have done it? How much more, when all he said to you was, 'Wash, and be clean'?"

5:14 So he went down and immersed himself seven times in the Jordan, according to the word of the man of God; his flesh was restored like the flesh of a young boy, and he was clean.

________________________________________

Sermon

I took the second of two required courses on preaching at Wesley Seminary during the summer of 2001. Ten or twelve of us gathered for an intensive, two week course, offered by Professor Bobby McLean, preaching teacher, a contemporary and friend of Martin King. We met every night for two weeks, and we each had to preach twice within ten days. There was little time to think, little time to breathe. We had to pick a couple of slots and pick our readings quickly. Picking became a matter of instinct--one reading had to be from the first testament--the Hebrew scriptures--and one reading had to be from the second testament--what some call the New Testament.

It came time for me to pick a topic and reading, and I remembered a conversation I had the week before with my best seminary friend, Amy Yarnall. We spoke by phone on July 3rd. I was in Washington. She was in Wilmington Delaware, where she served a Methodist church. What are you doing, I said. “I am trying to write a sermon before I head to the beach with my family.” Oh what is it on? “The healing of Namaan.” The healing of what? It a story from 2nd Kings, full of drama--prisoners of war, feuding kings, leprosy gained and lost. I remember being intrigued and resolving to read the story. It was fresh in my mind when Professor McLean asked what we wanted to explore. I’ll do Namaan, I said.

The night came to preach and I preached the Namaan story. Namaan is a mighty warrior and he is seriously in a bind. He is beloved by his king for his bravery and his military know how. Recipient of the prizes of conquest. He was Dick Cheney. He was Colin Powell. There was only one problem. He had bad skin, really bad skin--Leprosy. You get the sense that he has looked and looked for a cure.

One of his war conquests is a little slave girl belonging to his wife. She mentions one day that she knows a prophet in Samaria that could take care of his situation.

This is a great inspiring text--Martin Luther King loved it--because it says, Now what have we come to here? The mighty warrior having to listen to the little nobody, the little slave girl without a name, a foreigner, a prisoner of war. This mighty warrior is powerless to find his way to wholeness and health and restoration without being forced to listen to the most marginalized character possible. And the king can’t help either.

So Namaan listens.

I was preaching The Namaan story now in the summer of 2001 at Wesley Seminary, and I tell a story in this sermon about Henry Nouwen--beautiful Catholic writer and his recollection of going to Selma. He was working as a chaplain in Kansas at the Menninger Clinic, when King put out a call for all clergy to come down to Selma. Nouwen heard the appeal, but ignored it. And soon he became restless in his spirit. His sleep was interrupted, often, by the question gnawing at his spirit, “Why aren’t you in Selma?” He had many good excuses and all of his friends said that his desire to go to Selma was a desire for excitement. He says that he had to decide how and to whom he would pay attention. He got in his car and drove down to Selma. In Vicksburg, he came upon a black man standing at the side of the road, Charles, aged twenty. “God has heard my prayer.” Charles said as he piled in Nouwen’s car. I’ve been standing here for hours and nobody would pick me up. No one saw me, or when they did they tried to run me over. But I prayed and prayed to get to Selma and now here you are. My answered prayer.

Nouwen took a chance and heard a remarkable tale of five imprisonments, the death of his friend Medgar Evers. He heard about conditions in Mississippi, and as this stranger kept talking a deep fear rose up within Nouwen. He said out of that fear I received new eyes to see, new ears to hear.

Who we listen to matters on the road to healing and peace, I preached that July evening. Namaan found that out. So did Nouwen. And what we see depends a lot upon where we stand. If Nouwen had not decided to get in that car and drive down to Selma, he never hears Charles story. His life is never touched by this completely different person than he, the very definition of the other. If he hadn’t decided to take a stand and stand in a new place, his life may have turned out very differently. Where we stand depends on what we’ll see and who we’ll hear, on our road to peace.

Where we stand is determined by any number of factors--the color of our skin, the degree of our financial security. It has a lot to do with class. Middle classs white people in America are desperate to believe that all is well, and we do what we can to reinforce that belief. SINCE WE WON’T EASILY CHANGE THE PLACE WHERE WE ARE STANDING, WE WILL AT LEAST HAVE TO START BY LISTENING TO PEOPLE WHO ARE STANDING SOMEWHERE ELSE AND ASK THEM WHAT THEY SEE.

Well, my sermon went on like that for a while. I preached on Nouwen’s reflections on who arrived there in Selma, “God’s fools he said. Social outcasts. Crazy, odd characters. Not a cent to their name but they came to march with the oppressed in Selma.

I delivered my sermon. All of the students gathered round in a circle. Bobby McLean said, I was at Selma. There were some odd characters there. I remember, he said in his old, somewhat still Southern African-American voice, I remember one night Martin looked at me and said you’re preaching tonight. Professor McLean said that night my text was Namaan. That rocked my world.

The Namaan story put me on a quest for deep reflections on the nameless, the voiceless, the marginalized. The first thing you notice in that story is that slave girl’s namelessness, her total lack of status. But also that she holds all kinds of power, if she would just be heard.

So I went off on a quest for reflections on the nameless, the voiceless those easy enough to ignore.

I soon encountered W.E.B. DuBois, James Baldwin, Toni Morrison. It is W.E.B. DuBois that identifies a great veil, a veil that separates the white world and the black world. “How does it feel to be a problem?” So said a little white girl to W.E.B. DuBois while he was but a little boy. And from there he begins a lifetime reflection on what it means to be black in America. To have to see oneself through the eyes of the other world. As my professor of systematic theology writes, “It hit Dubois. A little white girls’ particular embodiment of the question stung him into the realization that he was “Shut out from the white world by a vast veil.”

From the instant DuBois encountered that little girl and her question, he began to exercise an inner strength; he began to assert his will within the veil. He embraced this veil which shut him out of the mainstream. Through that veil he gained insight into his world, into himself and into the other world.

Toni Morrison’s collection of essays, really lectures, Playing in the Dark, comes to illuminate a will that refuses to see the self through the revelation of the other world, the white world. While DuBois said that one ever feels this twoness--an American, a Negro. She writes, “American means white, and Africanist people struggle to make the term applicable to themselves with ethnicity and hyphen after hyphen after hyphen.

Playing in the Dark argues that white America, as reflected in the white American novel, reveals America’s ambivalence toward blacks. She aptly calls this ambivalence American Africanism, which signifies an entire range fo views, assumptions, readings and misreading that accompany Eurocentric learning about black people.

This veil plays out in this way, according to DuBois. The problem of anti-black racism, means that the African American in order to have a true self-consciousness, must constantly measure self consciousness against racist images. It is peculiar sensation, DuBois writes, this double-consciousness, this sense of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.

His question, How is it possible to be both black and American, is the very heart of Baldwin’s entire writings--America means white, Baldwin always said, and is the heart of Playing in the Dark as well.

The old Anglo-Saxon world is at the root of those views, assumptions, readings and misreading that define white attitude towards African Americans. The phrase that Morrison uses is American Africanism, which captures nicely the misreading by whites (Americans!) of people of African descent. The old pioneers in search of the city of God, Morrison argues, fled apostate lands, and came after adventure. Here, the desire for freedom is preceded by oppression; a yearning for God’s law is born of the detestation of human license and corruption, the glamour of riches is in thrall to poverty, hunger and debt. The pioneers in other words sailed to America in quest of a blank slate. But she argues this land that would wipe the slate clean and make possible a new beginning was inlaid with the Old World’s contradictions: Those who had bowed low to the Crown became sovereign, the vassal became powerful. The tension she identifies in this way:

One could be released from a useless, binding, repulsive past into a kind of history-lessness, a blank page waiting to be inscribed. Much was to be written there: noble impulses were made in law and appropriated for national tradition; base ones, learned and elaborated in the rejected and rejecting homeland, were also made into law and appropriated for tradition.

In these essays, Morrison wants to show how in America this tension between noble and base impulses gets to be explored in popular fiction--Herman Melville, William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, through the slave population.

In those writings, time and again the characters of color are nameless, are speechless except in cases where the white person is served; and are mythical--either savage or harmless servant. The Namaan story, writ over and over.

In Morrison there is a deep African american spirituality, what my professor defines as the African American’s ability to see from within the veil, that is to see one’s own virtue and one’s oppressors vices and to rail against anti-black racism because of a dogged inner strenth. The spirituality of Morrison is this: the insight is this: that the pendulum exposed in white literature about African Americans--jungle savage or harmless servant--exposes and measures the souls of white folk, not the souls of black folk.

Out of that veil, you see Morrison comes to a place of liberation and freedom.

Because she wishes to be healthy, not racist, Morrison has forged a well integrated self-consiousness, within the veil. She knows she is a problem to the other world, and overcomes two warring ideals lest they break her: Fate has mined her American language with “hidden signs of racial superiority, cultural hegemony and dismissive othering. How to render blacks truly? How to maneuver ways to free up the language from its sometimes sinister, frequently lazy, almost always predictable employment of racially informed and determined chains. Living in a nation of people who decided tha their world view would combine agendas for individual freedom and mechanisms for devastating racial oppression presents a singular landscape for the writer. So, we get from her, from her wisdom within the veil, Beloved and the Bluest Eye. We get from her the beautiful image of her holding up the mirror so that white america might yet see.

Of course, the person that we celebrate on this day, did that very thing, within his own veil in the middle half of the 20th century. And that of course is the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King.

When King was a student at Boston University, the big theological foundation there was called Personalism. One other thing that Bobby McLean my preaching professor told me was that a whole slew of African American students at Boston nearly became Unitarians, because of this idea of personalism. In fact, Bobby McLean spent half a year as the interim at First and Second in Boston, one of our oldest Unitarian parishes. Personalism gets right to what we are talking about here around the whole issue of Namaan and the slave girl, and DuBois, Baldwin and Morrison and their veil. Personalism is a uniting theology that says, at the root of all of theological reflection, must be a deep and abiding respect for the human personality--unique, divine and of ultimate importance. The idea of the human person is tied up with the idea of the Divine Person---that the divine person is diffused if you will in each human being and therein lies our optimism about humanity’s movement toward the good.

This kind of image of God in all persons is related to what Forest Church suggests might be the best model of God in the 21st century--the hologram, no matter how much it is split up, it still works. It still has impact.

The great question, this cycle of the Commission on Appraisal, the body that looks at big issues confronting Unitarian Universalism is this: Is there a core to our faith. I nominate Personalism. King never really left personalism as a theological construct, though he modified his view of human nature over time to be a tad more realistic. That the human personality is ultimate because each carries the image of the divine is a unifying faith of an unrepentant liberal.

The second thing King does is remind us that the church has power, social power in social contexts. A famous quote: The gospel at its best deal with the whole (person), not only his soul but his body, not only her spiritual well being but her material well being. Any religion that professes to be concerned about the souls of men and is not concerned about the slums that damn them, the economic condition that strangle them and the social conditions that cripple them is a spiritually moribund religion awaiting burial.

The last thing that I want to say about King is that he had hope. He believed in the coming of justice and peace. He believed that God worked in history--as did our greatest Unitarian thinkers--Theodore Parker, James Luther Adams, Channing. In his speech, Facing the challenge of a new age, King wrote: I have talked about the fact that God is working in history to bring about this new age. There is the danger that after hearing all of this you will go away with the impression that we can go home, sit down, and do nothing, waiting for the coming of the inevitable. You wil somehow feel that this new age will roll in on the wheels of the inevitable, so that there is nothing to do but wait on it. If you get that impression you are the victims of an illusion wrapped in superficiality. We must speed up the coming of the inevitable.

To speak of God working in history is to speak of concrete human experiences, concrete human dilemmas, especially around social and political power.

A time for confession. I believe that my personal political views need not dominate the views of my sermons--I believe, in other words, that there is room within Unitarian Universalism for all kinds of political views and we are called to be the church not to be a political action committee. But I do believe that politics and religion sometimes meet, as in King’s Letter to a Birmingham jail, and there are times when the minister must address concrete political realities. The confession is this: In this day, it is perhaps an overwhelming task.

I survey the Administration in power and I do not know where to begin. I need your help. I cannot do it all alone. We need to build this place into a laboratory for the human spirit and that means that we must all take up the important, concrete questions and issues of our day.

Are you most concerned with the secretiveness of this administration? The clinging close to the chest information about how decisions are made about war, about Iraq, about Korea? About Columbia, the Phillipines? I grow concerned.

Are you most concerned about the unilateralism, the kind of Texas stagger that insists that we need not have our allies on board in order to go to war in Iraq?

Are you most concerned that the victims of repression--Iraqis and Afghanis and North Koreans are going to hear that the only solution we can come up with are additional weapons of mass destruction, that our imagination is so limited that we can conceive of no other way out of this mess?

Are you concerned that the Democrats have completely lost their way?

Are you concerned that there is a war on the poor in this country, that as we speak social safety nets are being quietly and efficiently taken away?

This King that I lift up on this day is one that asks us to respond to the fierce urgency of now, in love and faith and hope. Asks us to ensure that we remember the dignity of each person, the call to compassion and hope. That everyone might have a voice, that everyone might have a name, that everyone might have peace.

Labels: Anti-war sermon, Bobby McLean, liberal christian, Namaan, unitarian universalism